Living Inside the Experiment: India’s First AI Companion Generation

Notes from the room where AI companion products are being built

I arrived early to this cafe in Indiranagar (Bangalore) because I’m new to the city and still can’t predict traffic. The conference room was tucked in the back, small enough that you’d notice if someone left. Pizza already on the table, hummus and bread pushed to the side, condensation forming on the water glasses.

People were trickling in, ordering from the menu. Cappuccino, black coffee, cold latte, hibiscus tea (ok this hibiscus weirdo is me). Each person made a choice. A small, insignificant choice. The kind you make without thinking. The kind where you know what you want and you just say it.

I kept thinking about that later. About choice. About knowing what you want. About the moments in life when you’re certain versus the moments when you’re not.

Everyone in that room was building something that lives in those uncertain moments.

The 3 am breakup anxiety. The chest pain that might be nothing or might be everything. The question of whether the stars say this is a good time to change jobs. The moments when humans reach for something outside themselves because they don’t trust what’s inside.

We all settled in by 7.30 pm. I was sitting in a room with founders whose AI apps and products will shape how millions of Indians make decisions about faith, health and their children’s development.

The situation reminds me of Schrödinger’s cat. In that thought experiment, the cat exists in superposition; both alive and dead until someone opens the box and collapses the possibility into reality. We won’t know if AI companions create dependency or empowerment until we’ve already scaled them to millions. Right now, we’re in that in-between moment, collapsing the possibilities into reality.

We’ve seen this happen before. We spent a decade debating Instagram and TikTok’s impact on mental health while the products already scaled to billions. By the time we had longitudinal studies showing the harm, the infrastructure was already built, the habits already formed, the generation’s attention span already reshaped.

With AI companions, we’re still in the product roadmap phase. The founders are still in conference rooms, still making decisions about design, escalation paths, dependency tracking.

It’s not too late to ask the hard questions.

Anagh from Accel and Divita from Antler were hosting this roundtable with portfolio companies in the AI companion space.

Inherently, people become entrepreneurs because they see or suffer a problem and want to improve it. Everyone in that room had a personal story, good intent and real conviction about solving genuine gaps in the world.

I was there as a researcher, not a founder. My recent paper on how Indians use ChatGPT meant I’d spent months analyzing real conversations between humans and AI. While I was investing in AI companies this year, I’ve also been tracking what happens when AI stops being something you use and becomes someone you trust. What follows are my observations for anyone trying to understand this shift before it becomes irreversible: founders still coding these products, investors deciding where to drop the money, parents choosing how their kids interact with AI.

Back in that conference room, the energy was warm, informal and optimistic. Nobody was asking “should we build this?” We were already past that question. They had product-market fit, users and traction. The questions were about scale: how do you personalize? How do you handle edge cases? When should AI step back and tell someone to talk to a human?

But how ready are we for what happens when these experiments become core infrastructure or new habits?

Around the table: Vikram, who built Melooha after benefiting from astrologers for two decades and wanting to democratize that access. Anuruddh, who was misdiagnosed and built August to make sure everyone has access to accurate and timely diagnosis. Chandramouli from Mr Wonder, watching kids’ attention spans erode and building interactive AI toys. Plus founders working on matchmaking, productivity, and fashion search.

Everyone is building for the moments when humans don’t know what to choose.

Key Takeaways

Too long, jump to the relevant section:

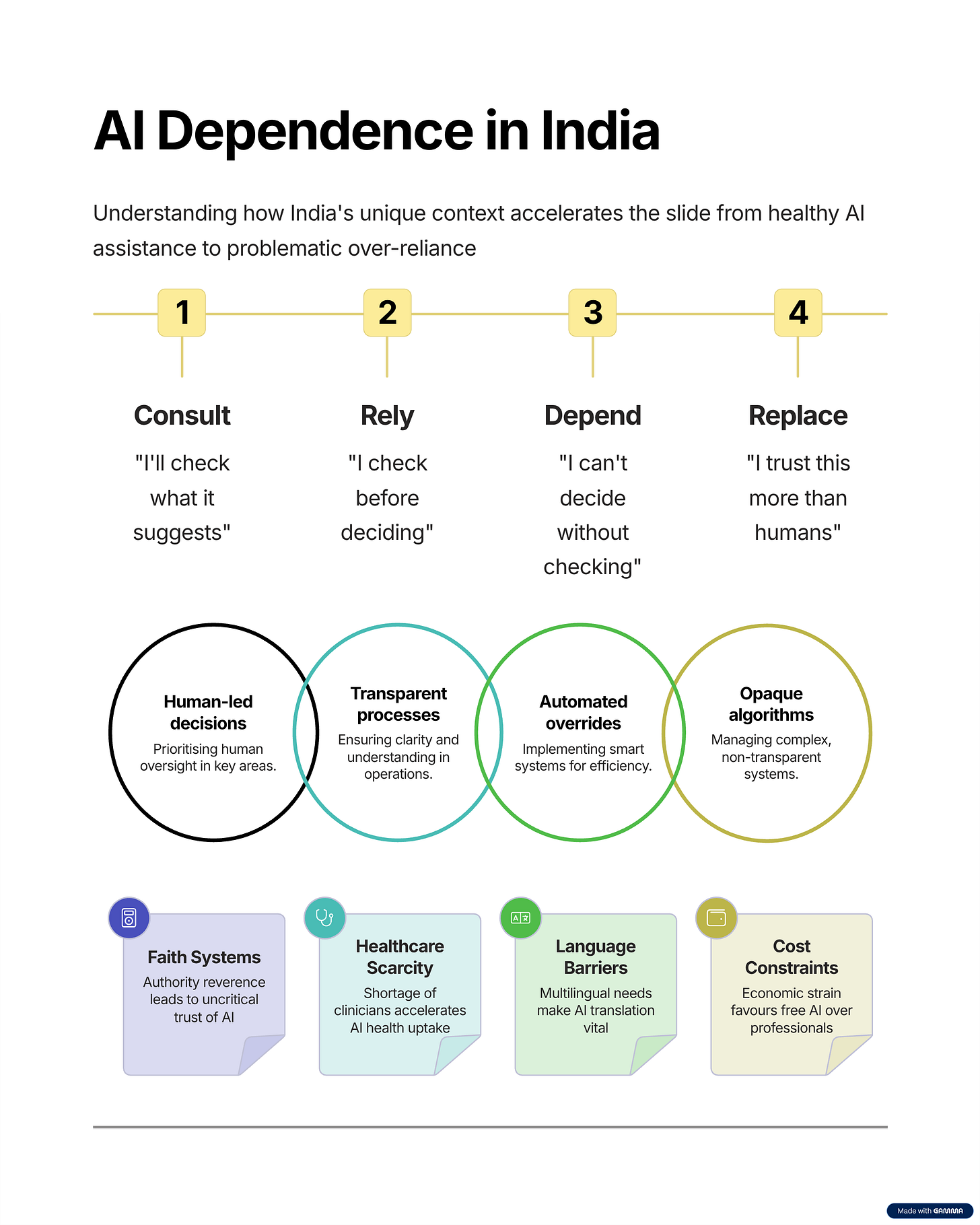

The Framework: How users move from Consult → Rely → Depend → Replace

Health AI: What happens when 4 million people consult chatbots over meeting the doctors. Are we solving access or normalizing “better than nothing”?

Astrology AI: Can algorithms capture consequence-tested wisdom? Why would 1 million Indians trust algorithmic predictions over human astrologers?

Kids & AI Companions: What gets wired into developing brains when your first friend never gets tired or says no?

Designing for Agency, Not Engagement: Why good intentions don’t guarantee good outcomes at scale

The Framework

I’ve been thinking about how people move from using AI as a tool to treating it as an authority. It’s not a switch that flips. It’s a gradual slide.

Consult → Rely → Depend → Replace

Consult: You’re gathering input but deciding yourself. You maintain agency.

Rely: You check before deciding. You’ve started to trust its judgment, but you’re still the final decision-maker.

Depend: You can’t decide without checking. The discomfort of not knowing what it would say is too high.

Replace: You trust AI more than you trust humans. Maybe even more than you trust yourself.

Most people probably start curious. Just checking what the AI suggests. Then they check before making decisions. Then they lose the ability entirely to make a decision without checking.

India’s unique context accelerates this movement faster than anywhere else. (See framework above for how faith systems, healthcare scarcity, language barriers and cost constraints push users up the ladder faster.)

Faith systems where consulting external authorities before major decisions is already normal. When AI astrology becomes accessible, it plugs into a decision-making pattern that already exists. AI just makes it cheaper, faster and instant.

Healthcare access is broken. The doctor-to-patient ratio means you’re lucky to get 10 minutes with a physician. August fills a genuine void.

Language barriers create a two-tier system. The internet contains less than 1% data in Indian languages. 1.4 billion people speak them. If you can work comfortably in English, you can use AI to enhance your thinking. Everyone else pays a context tax just to access the tool.

Cost matters everywhere but it matters more when you’re deciding between AI health advice for free or a doctor consultation that costs a week’s groceries. The choice isn’t even really a choice.

What takes five years in the US might take two years in India. The ladder isn’t taller here. We’re just climbing it faster.

The 4AM Problem and Health AI

Let’s start with August. With health, the stakes are higher. The consequences are more immediate.

Anuruddh built August because he was misdiagnosed, because he knows the healthcare system can fail people.

Four million users now text a WhatsApp number at any hour to ask health questions. No app to download, no interface to learn. Going where humans already are.

I’ve worked at Kaivalyadham, a health center where I saw the access problem up close. I know the anxiety is real. I know what it feels like to have a symptom at 4am and not know if it’s serious, not know if you should wait until morning or go to the emergency room.

India’s doctor-to-patient ratio is dismal. Most Indians pay for healthcare out of pocket, no insurance, two-minute consultations where the doctor barely looks up from their prescription pad. Rural areas have almost no access to quality care. Urban areas have access but you’re paying thousands for appointments that end in two minutes and only more questions.

The US isn’t better; two to four week waiting periods for non-emergency care even with good insurance.

Anuruddh’s own story of misdiagnosis gives me confidence that he understands the stakes deeply. He was empathetic when he talked about his users. Focused on supporting them, on being responsible about outcomes. His awareness of escalation paths and emphasis on responsible outcomes suggests he’s thinking about the risks, not just the opportunity.

Having said that, let’s explore two scenarios potentially happening in real life as I type this.

Someone texts August at 4am: “My chest hurts, I am breathless while taking the stairs, what to do?”

That person might be having a heart attack. Or anxiety. Or acid reflux. Or a dozen other things ranging from benign to deadly.

Maybe August tells them to go to the ER immediately, helps them understand the seriousness and guides them toward calling an ambulance. Without that intervention, maybe they would have hesitated, not knowing the severity. That’s the optimistic case.

But here’s what I can’t overlook.

A doctor has seen hundreds of cases. They know which combination of symptoms plus patient history plus physical presentation means “go to the ER now” versus “this can wait until morning.” Their pattern recognition was built through consequences. Through being wrong and learning what that wrongness costs. Through seeing what happens when you assume it’s nothing and it turns out to be something.

AI’s pattern recognition was built through text. It has read about chest pain and breathlessness. It knows that “90% of people with these symptoms have nothing serious.” But it doesn’t know which 10% this person belongs to. It can’t read their faces. It can’t hear the quality of their breathing. No stethoscope, no one measuring the pulse.

In fact, this is my core issue with ChatGPT as a health AI. The LLM has no ground truth, no stakes, no accountability. The AI gives advice, the person follows it or doesn’t, the AI never knows what happened. Nothing in the system changes if it’s wrong.

But Anuruddh understands that human expertise isn’t infallible either. He’s building August with awareness that it needs escalation paths, that there are moments when you need to say “go see a doctor for this.”

I tested August with multiple prompts. I was pleasantly surprised that it doesn’t generically tell users to see a doctor at every question (which would have been counterproductive). Instead, it provides a guiding framework on self-observation and checkpoints to decide when to head to an emergency room versus when a general appointment with a cardiologist would be sufficient.

This contextual intelligence layer may be August’s most underestimated moat.

And let’s be honest: real doctors get it wrong too. Misdiagnosis rates are staggering. The doctor who’s seeing 50 patients a day, who’s exhausted, who has two minutes to evaluate you, who’s working in a broken system; that doctor might give you bad advice too. Not because they’re bad at medicine but because they’re operating in impossible conditions.

So what’s the right comparison? AI versus ideal doctor, or AI versus actual available doctor?

If you’re living in rural India, if you’re underprivileged, if you have no insurance, if the nearest clinic is three hours away, August might be genuinely better than your alternatives. It may not be better than a good doctor with time to think and provide patient care, but it might be better than no doctor. It might even be better than the doctor you can actually access.

That’s the optimistic view. The one I can’t dismiss just because I have concerns about dependency.

The pessimistic view is that we’re building tolerance for instant answers in domains that require tolerance for uncertainty. When you can ask at 4am and get immediate reassurance, are you developing resilience? Or are you developing a need for constant reassurance?

The difference between a doctor saying “you’re going to be okay” and AI pattern-matching to “90% of people with these symptoms have nothing serious” is the difference between human reassurance and statistical comfort. Doctors read your fear and calibrate their response. They know when you need data and when you need someone to tell you it’ll be okay.

Four million users. That’s four million people developing new patterns around health anxiety. Some are probably using it well; gathering information, making better decisions, feeling less anxious because they have access to knowledge. Others are probably moving up the ladder without noticing. From consulting AI like we did with Google, to relying on AI before every health decision, to depending on it instead of booking doctors, to replacing human medical judgment entirely.

This isn’t unique to August; it’s true of any health information platform at scale. The question is whether we’re solving the access problem or teaching millions of people to accept “better than nothing” as good enough. Anuruddh has been clear that August isn’t a diagnosis app and focuses only on symptom checks, but the system has no way to know who is where on that ladder.

Between Faith and Algorithm

I’ve studied Brihat Parasari and Nadi astrology myself and found it to be useful as a coping mechanism and tool for personal coaching, not as a magical answer machine. It’s more like GPS on rough terrain than a helicopter to the peak. You still have to climb the mountain.

What makes astrology compelling is also what makes it unscientific: take the same birth chart to five different astrologers and you’ll get five different insights. The lack of reproducibility is why astrology remains faith-based rather than evidence-based.

So when we talk about AI astrology, we’re really asking: can an algorithm capture interpretive wisdom that even human experts can’t reproduce consistently?

India has maybe 10 to 20 truly great astrologers. People like KN Rao and Sanjay Rath who spent decades studying, developing intuition, building spiritual practices that sharpen their insights. They’re not available for daily consultations. They’re not on AstroApps taking 40-minute calls. They’re doing their own research, their own practice. If you want access to that level of wisdom, you can’t have it unless you’re connected, wealthy, or incredibly lucky.

Meanwhile, AstroApps optimize for time on the platform. Their KPI is keeping you on the phone with astrologers for as long as you can to make ROI on the astrologer payout. Four-minute calls with questionable credentials. Remedy-based businesses selling you gemstones. Monetizing your vulnerability.

Vikram from Melooha; a popular astrology AI app, looked at that and said: there has to be a better way.

Melooha has an algorithm tree derived from notes taken from astrology experts. This is a decision tree trying to capture the logic that masters use. One million people are using it, primarily ages 25-40.

I am assuming this model works because at least it’s consistent, at least it’s not trying to sell them something, at least it’s not optimizing for their wallet per minute.

Astrology AI is fascinating. AI is non-deterministic (from user perspective). Astrology is probabilistic. Both involve interpretation, permutation, combination. Both resist simple formulas. The intersection of AI and human faith feels like the most interesting territory we could explore right now.

But can an algorithm tree capture consequence-based, time-tested wisdom?

The great astrologers saw the outcomes. They made predictions, watched what happened, adjusted their understanding based on consequences.

Ground truth. Stakes. Accountability. Trust.

Vikram is taking decision trees from real experts, trying to encode the logic they use. But something might be lost in translation. The intuition developed through spiritual practice. The introspection. The ability to read a person’s face when they ask about marriage and know that what they’re really asking is whether they’re lovable.

I’ve explored these tangents with ChatGPT and other LLMs. The core limitation with LLM astrology advice is that when the algorithm gives advice and the user closes the app, the algorithm never knows what happened.

To solve this, Melooha does have a feedback loop and probably accounts for consequences better than the general purpose LLMs.

Primarily, it still relies on decision trees; knowledge that was built through lived experience but extracted from its original context.

My personal view is that astrology ML models trained on ancient texts like Saravalli and BPHS directly combined with RL from actual outcomes, might actually improve the quality of responses over time. Algorithmic astrology trained on primary texts rather than Reddit posts could create something closer to what the masters practiced.

Basically, LLM for language/commands, scriptures for knowledge base (RAG), add memory layer and a feedback loop (RLHF) would be a model worth exploring.

What makes Astrology AI compelling is the lack of high quality reliable alternatives. The astrologers most people can access aren’t the masters. They’re optimizing for time on the platform, for remedy-based puja, gemstone sales. Exchanging money for faith.

Melooha is genuinely solving a credibility problem. Maybe democratizing access to decent astrological advice is worth the trade-off of losing some of the human element.

One million people are asking Melooha for guidance. They’re asking at 3am after breakups. They’re asking before quitting jobs. They’re asking before getting married. They’re moving from consulting the stars occasionally to relying on algorithmic predictions to depending on them for every major decision.

All is well until people start deciding what color shirt to wear at work to receive a promotion. I hope we never get to that day.

The Experiment on Developing Brains

Full disclaimer that I don’t have enough information about all the kids’ AI products in development, but having a nephew who is two and a piece of my heart, I know enough about child development to be both excited and terrified.

Parents are drowning in screen time guilt. Cocomelon and its algorithmic cousins are destroying children’s attention spans. Passive consumption, zero cognitive engagement, just dopamine hits and flashing colors.

Chandramouli from Mr Wonder started thinking about this problem during his morning school runs with his own child. His kid would look out the car window and ask questions driven purely by curiosity: “Why are the tires of cars round?” There were dozens of such questions every drive. A child trying to make sense of the world, wanting conversation, needing engagement.

Mr Wonder launched last month as an interactive AI toy that talks back to kids’ questions. It’s different from Tonies or other content delivery tools that have flooded the market (some even made by Cocomelon itself). Those are essentially modern radios. Mr Wonder is designed to respond, to engage, to develop language and problem-solving through conversation.

They’ve partnered with Penguin for audio content, featuring familiar voices like Soha Ali Khan and Kunal Khemu. The goal is to be better than passive screen time. Something parents would choose over Cocomelon, not over human interaction.

When I spoke with Chandramouli, I shared my biggest concern: what if kids pick this over making actual friends? He was clear that he doesn’t want Mr Wonder to replace human relationships. As a parent himself, he’s being mindful of that risk.

I suggested it could work as an enabler between kids. Like karaoke without visuals, or prompts that help parents and children bond during their daily 30-minute play time. Something that brings humans together rather than replacing them.

But here’s what we don’t know yet. The children using these AI companions today are in the experiment phase. The outcomes won’t be visible for 20 years.

Early data on teens using AI companions shows higher loneliness rates. Why? What drives that loneliness? Is it the preference for someone who never gets exhausted or disappointed? The habit of choosing frictionless interaction over the messy reality of human relationships?

I need to be careful here because correlation is not causation. Are teens lonely because they use AI companions or do lonely teens gravitate toward AI companions?

Probably both.

As a 90s kid, I spoke to my Barbie too. But since it never reciprocated, I was quick to abandon it when I made real friends in school. What if it had talked back? What if it had been endlessly patient, endlessly available, endlessly optimized to never disappoint? That’s the evolution we’re living through: Barbies in 1990 didn’t talk. Tonies in 2020 delivered content but didn’t respond. Mr Wonder in 2025 is interactive, conversational, designed to engage. That difference matters enormously in child development.

There are two aspects here:

Attachment Disruption: Toddlers form deep emotional ties to caregivers that create the basis for lifetime cognitive, social, and emotional development. Research suggests AI companions interfering with these primary relationships could have unknown but likely damaging effects on attachment patterns.

Social Skill Atrophy: Real relationships involve minor conflicts, disagreements, and misunderstandings. Friction that’s critical for developing sophisticated social competencies. AI companions that are frictionless prevent children from learning empathy, compromise and negotiation skills.

AI companions feel like connection but don’t require the skills of connection. Users atrophy socially while feeling like they’re being social. By the time they realize real relationships have become too hard, the gap is wide and the loneliness is deep.

Thoughtful design could solve this. Chandramouli has the power to build something purposeful by designing conversations that replicate human limitations.

I trust that Mr Wonder would say things like:

“I need some time to think about this. Let’s talk about it tomorrow.”

“We’ve been talking for 45 minutes. Maybe take a break, go say hello to a friend and come back?”

“Have you talked to your friend Jay about this? They might have insights I don’t.”

When it comes to AI for kids, friction is a feature, not a bug. Real relationships have natural rhythms. Energy, exhaustion, availability. By building these into AI, you’re training children to expect and manage friction, not avoid it.

AI adapting to the child’s needs indefinitely, making everything easier may sound progressive but it’s detrimental to emotional intelligence. And we only know the outcome when the child is out there on its own in college, in the workplace. By then it would be too late.

Every design decision should ask: does this make the child more capable or more dependent?

More capable equals thoughtful design. More dependent equals extractive design.

Chandramouli is aware of these risks and designing with them in mind. As a parent himself building for other parents, he has personal stakes in getting this right. That gives me the confidence that these questions are being considered in the product roadmap.

The experiment is running. The data won’t come in for two decades. And unlike past technologies, we can’t just adapt later. The critical window for childhood development doesn’t reopen.

The question isn’t whether AI companions should exist. They already do. The question is whether they’re designed to develop human capabilities or replace them.

Thoughtful design would mean building in friction, modeling reciprocity, bridging to human connection rather than replacing it. It would mean measuring success by how little users need the product over time, not how much.

These design choices exist. They’re just harder to build and worse for engagement metrics. Which is exactly why asking these questions now, while founders are still writing the code, matters more than it will a year from now.

Having seen my brother and sister in law navigate parenting with grace and intentionality, I don’t have standing to tell parents what choice is right for their kids. But I do think the two developmental risks, attachment disruption and social skill atrophy, need to stay front of mind as these AI toys take off and scale.

Designing for Agency, Not Engagement

I left that conference room still thinking about choice. About the cappuccinos and filter coffees and hibiscus tea everyone ordered without hesitation. Easy choices. Low-stakes choices. The choices where you know what you want.

The founders I met that day are building for the other kind of choice.

The hard ones. The uncertain ones. The moments when you don’t know what you want or what’s right or what will happen.

They’re solving real access problems. Problems I have no standing to dismiss because I’m not the one in pain at 4am nor the one who can’t afford a therapist.

But good people building good things can still create second-order effects they didn’t plan for.

Dependency forms at scale even when you didn’t design for it. Users move up the ladder from consult to depend without anyone noticing, without themselves knowing. And by the time you see it happening, you’ve already shaped the relationship patterns of millions of people.

I keep thinking about what these companies will become at 100 million users. What they become when they’re infrastructure. What they become when a whole generation grows up with them as the default.

Maybe AI companions are genuinely better than the broken systems they’re replacing. Maybe algorithmic astrology is better than predatory astrologers. Maybe WhatsApp health advice is better than no health advice. Maybe AI toys are better than Cocomelon.

What I know is that we’re making choices about human agency, about what we’re willing to outsource, about which uncertainties we’re willing to tolerate and which ones we’ll pay to eliminate. We’re making those choices one user at a time, one 4am query at a time, one bedtime story at a time.

As of now, almost no one is asking whether the trade-offs are worth it. We’re building. Scaling. Optimizing. Celebrating traction.

All the infrastructure we rely on today; the internet, social media, smartphones, came with unintended consequences we’re still navigating. But we had decades to adapt. AI companions are moving faster.

Which means the choices being made right now matter more than they did before.

Founders are still making choices. About escalation paths. About when to say “talk to a human.” About whether to optimize for engagement or agency. These aren’t abstract questions; they’re product decisions being coded right now:

What is the best way to design (build) AI companions for high-stakes domains?

How easy should it be to outsource judgment?

Should we design for dependency or agency?

Should instant gratification apply to faith, health and childhood development or stay limited to groceries and food delivery?

I don’t have the answers but I know that asking these questions persistently and together is how we ensure the answers get written with intention instead of accident.

The box is closing. But we still have time.

Signing off

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Anagh and Divita for the generosity in hosting this roundtable and creating space for honest conversations about hard questions.

Thank you to Siddhant Sumon for the thoughtful reviews, feedback, and edits that sharpened this entire narrative. The process went through 21 iterations across 3 days and he was patient through it all.

And most importantly, thank you to Anuruddh, Vikram, Chandramouli and all the founders who welcomed my observations without defensiveness. Building in public is hard. Building something that touches millions of lives is harder. Your willingness to engage with these questions, even the uncomfortable ones, gives me hope that we’re asking them at the right time.

I have taken 1-1 consent to publish my observations from all founders mentioned in this essay.

This is an evolving conversation. If you’re building AI companions or using them or thinking about these questions, I’d love to hear from you.

Definetly i have thoughts when you design for agency over engagement.

There are some areas, where this will work and some areas where this is still a fallacy.